Corey Orvold is not a typical whistleblower.

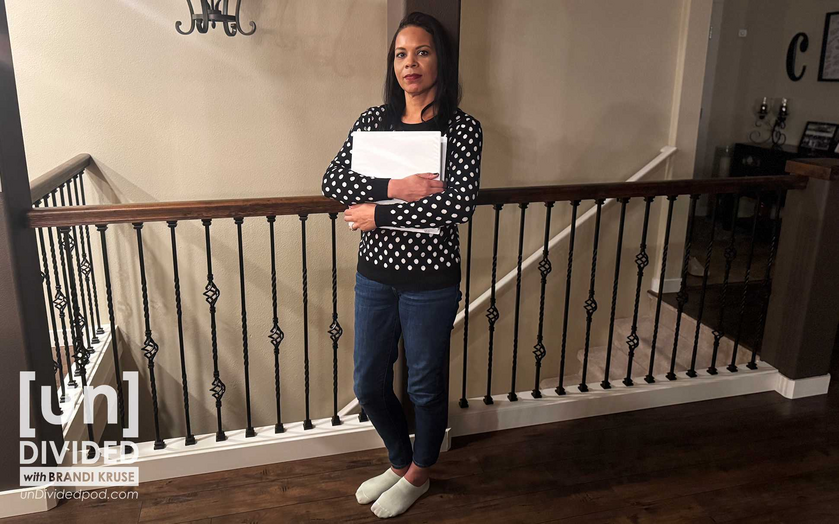

When I pulled up to her Puyallup home a few months ago, expectations were low. Journalists will tell you they get dozens of tips a year from people who claim they have evidence of corruption, fraud, or waste. Few, if any, turn out to be worth pursuing.

But there, in her garage, Corey met me with a 3-inch-thick binder. In it, was evidence of her 10-month-long mission to expose self-dealing within a program she once hoped would help black people achieve home ownership and build generational wealth.

Washington’s Community Reinvestment Program was created in 2022, passed into law by the Democrat-led legislature and given an initial $200 million investment. The program received another $50 million in funds for 2025-2027, despite a roughly $15 billion budget shortfall that resulted in Governor Bob Ferguson signing the largest tax increase in state history into law.

The funds are meant to help people of color – black, Latin American, Native American, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander – get home and business loans, foreclosure prevention, make home repairs, and even pay off credit card debt.

The program promised to “uplift communities disproportionately harmed by the war on drugs … to create lasting economic benefits, build wealth and ensure everyone has a fair chance at success.”

Instead, evidence shows the money is being used to enrich those with direct ties to the BIPOC nonprofits that now control its purse strings.

Suspicions grow

Corey, who is half black and half white, was introduced to the program as a real estate managing broker. If she had a client who met the criteria for Community Reinvestment Program (CRP) funds, she let them know they could qualify for down payment assistance. All they had to do was apply through one of several nonprofits that were given state contracts to award the money.

But Corey and others in real estate – many of them people of color themselves – kept running into problems.

Their clients were often told they’d have to work with a “preferred” broker or lender. Some were directed to apply, only to be told that money had run out. Others were given last-minute excuses why the help they qualified for didn’t come through: Their documents weren’t notarized, their account numbers were misplaced, the application wasn’t reviewed in time.

Something seemed suspicious. Corey, a former journalist, started digging.

Within a few months she’d compiled her massive binder of evidence – page after page of public records and home loan documents, many of them for homebuyers with a direct connection to the nonprofits entrusted with getting financial help to the community.

One of those nonprofits is the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle.

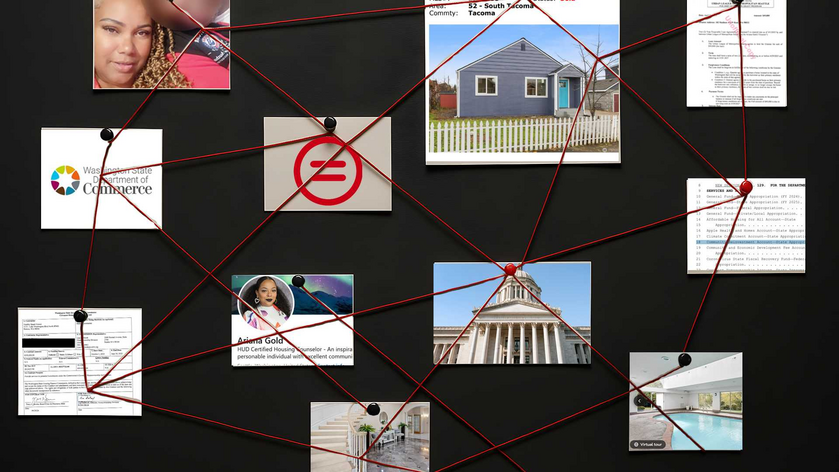

What follows is a tangled web of self-dealing that has now caught the attention of both the State Department of Commerce and the Office of Attorney General Nick Brown.

Means and opportunity

There is little doubt that homeownership across Washington state is out of reach for many. The average home price here is roughly $630,000, even higher if you buy in the Puget Sound area. For many young or first-time homebuyers, any amount of help would be welcome.

But how about $350,000 in “free” money to get you in the door?

Records show a woman named Aysia Williams closed on a Tacoma home for $424,950 on March 25, 2025. Thanks to multiple state programs that gift funds to people based on skin color, the actual amount of her home loan was only $89,960.

Aysia received:

$99,668 in funds from the Washington State Housing Finance Commission, which administers the newly created Covenant Homeownership Program, a reparations program designed to help first-time home buyers of color with downpayments.

$100,000 in Community Reinvestment Program funds from United Housing Resources.

$100,000 in Community Reinvestment Program funds through the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle.

$50,000 in Community Reinvestment Program funds through Byrd Barr Place, a Seattle-based nonprofit that says it works to decrease economic barriers and inequities.

That’s a total of nearly $350,000 to help just one person – most of it, courtesy of you the taxpayer.

The real kicker?

Aysia’s mom, Angela Williams, happens to be the Director of Financial Empowerment at the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle – one of the organizations that awarded her six-figures in down payment assistance.

Curiously, Angela Williams wrote in an email obtained by unDivided that the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle closed its downpayment assistance program to applicants in March 2025 due to a lack of available funds – just days after her own daughter used the money to buy a house.

And that is hardly the only time the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle handed out money to insiders while turning other community members away.

Ariana Gold is a HUD certified housing counselor for the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle. Records show that the organization awarded someone named Ariana Gold $49,800 to pay off consumer debt on April 29, 2025.

In the same email mentioned previously, Angela Williams said the debt reduction program also ran out of money in March – a month before Ariana Gold got approved for debt forgiveness.

Another home purchase closed with Community Reinvestment funds after the Urban League claimed to be out of money was for a woman named Tracy Brown. Tracy closed on a $640,000 home in Seattle in July. She was given $100,000 in Community Reinvestment funds through the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle and $145,341 from the Covenant Homeownership Fund, which is administered by the Washington State Housing Finance Commission.

Tracy Brown is the founder of an organization called Healthy Smart Homes, which was awarded a $350,000 contract by the Housing Finance Commission to help raise awareness for the Covenant Homeownership Program – which she went on to benefit from. The contract was also a direct partnership with the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle. Tracy would send potential homebuyers to the Urban League – which turned around and gave her $100,000 in taxpayer money.

Other, less connected buyers weren’t as lucky.

“He did everything he was supposed to do and got nothing,” said the mother of a 27-year-old first-time homebuyer who applied to get downpayment assistance with the help of the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle. The mother, who wished to remain anonymous, said ULMS strung her son along, then ultimately turned him away.

“My son broke down. Because he was so close,” she said. “Just to go through that was tough as a mother to deal with. This is a young African American man who has never been in trouble, has always worked since he was 16. Sometimes two jobs. He went to college, graduated from college. And this is what he was put through.”

She says she grew suspicious that the funds were being set aside for other, more connected buyers – like Aysia Williams, who was granted her downpayment assistance around the same time.

Surely, some of the $350,000 Aysia received to help purchase a home could have been spread out to help more people? Others thought so as well.

In March 2025, Byrd Barr Place Director of Strategic Initiatives Tiffany Kelly-Gray sent out an internal email with expanded eligibility guidelines for down payment assistance. In it, she warned against the layering of funding sources to help “a select few.”

Byrd Barr is one of several organizations tasked with distributing Community Reinvestment funds and awarded $50,000 to Aysia Williams around the time the email was sent out.

“We are committed to ensuring these resources are used effectively to expand access to homeownership opportunities. Not just for a select few,” Kelly-Gray wrote. “If you have a client currently in processing who intends to layer our program with another CRP-funded program, please inform us immediately so we can discuss next steps and ensure compliance.”

While the email didn’t explicitly mention Aysia Williams, or her connection to the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle through her mother Angela, it came shortly after Corey started alerting stakeholders to her concerns with how the program was being administered. The tone of the email suggested Byrd Barr was caught off guard by the layering of down payment assistance to help a single homebuyer – rather than funds being spread out to help many.

Playing favorites

Beyond direct assistance to employees and their family members, the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle played favorites with brokers and lenders – funneling clients to a select few.

In a text message shared with unDivided, one homebuyer told her loan officer she was advised “that I should work with one of the recommended lenders on the list. This was advised to me by the HUD counselor. She was stating that because of the intricacies and difficulties working with the program it would be easier to work with a partner that’s already worked with the Urban League.”

This practice allowed those “preferred” partners to profit off the program while those who weren’t “preferred” lost clients – and the resulting commission.

One lender listed as a preferred provider for the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle purchased an 8,270 square foot, $2.2 million home with an indoor swimming pool in Kent last November with her husband, a real estate broker. Before that, they lived in a modest house in Auburn.

Combined as a couple, they helped to close dozens of home sales funneled to them from the Urban League and other BIPOC nonprofits.

Presuming they’re not doing that work for free – business has been good.

In 2024, the real estate broker in question closed with 17 home buyers. In previous years, he averaged 10 or 11. In 2023, he closed on only 4.

In 2025 to date, he’s closed on 35.

Records show the couple was involved in closing the loan for Aysia Williams – one as the lender, one as the broker.

unDivided has chosen not to name the couple. While they are benefiting from the distribution of state funds, they are not contracted with the state and don't have a fiduciary responsibility to taxpayers. There is no evidence to date that they are giving kickbacks to organizations that send them business.

While it is unclear how they became preferred partners, social media posts show the couple is well connected. In one picture, the woman is standing in the backyard of her new mansion with State Representative Jamila Taylor – the architect of Washington’s Covenant Homeownership Program.

In some instances, preferred lenders and brokers are a part of the organizations responsible for handing out funds.

Nicole Bascomb Green, who is connected to multiple organizations with ties to the Community Reinvestment Program, operates a real estate brokerage out of her house. That brokerage employs several of her family members who have closed home purchases for clients sent to them through the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle.

In addition to being an Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle board member, Bascomb Green is also the chair of the Washington State Housing and Finance Commission, which helps administer down payment assistance programs.

“As a real estate broker, this does not preclude me from supporting my clients and their ability to use these great programs that have come out to support the people solely because they work with me,” Bascomb Green told us in an email. “I am proud to be able to support these programs and my clients who need these programs just like everyone else.”

She denied that the situation presents a conflict of interest.

“There is no conflict of interest because these interests have been fully disclosed to all parties, and in all my board affiliations. Everyone knows the work I do and where I do it, and there is nothing questionable about it.”

Down the rabbit hole

The Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle denies any wrongdoing. In an email, it declined to provide a list of all staff members, board members, or family members who have benefited directly from CRP funds, citing “privacy and confidentiality.” Without that list, which the state could presumably compel in an audit, it’s impossible to know how much money went directly into the hands of people with ties to the organization.

The list would, for example, settle suspicion around a foreclosure involving – once again – Angela Williams. According to county records, foreclosure proceedings were initiated against Angela’s Tacoma home in May 2024. The home foreclosure was rescinded in January 2025. At the exact same time, her employer – the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle – was using Community Reinvestment funds to save people from foreclosure.

Was one of those people Angela Williams herself? Asked repeatedly, the organization refused to say. Williams did not respond to our request for comment.

The Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle also declined to explain how funds were given out after March 2025, when Angela Williams is on record saying the programs had been depleted.

“ULMS is committed to transparency, accountability, and equity in all our programs, including the Community Reinvestment Program,” Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle President and CEO Michelle Merriweather told unDivided in an email. “ULMS assistance recipients must meet eligibility requirements set by the Washington State Department of Commerce. These standards are applied equitably to all applicants, regardless of employment or organizational affiliation. Sadly, many hardworking individuals, including those affiliated with community-based organizations, continue to face barriers to homeownership due to systemic inequities and high living costs.”

“We take concerns about program administration seriously and remain committed to upholding public trust and transparency in all our work,” Merriweather added.

Corey said she has included Merriweather on email threads detailing concerns with the program for months, to no avail.

“I want accountability, even if it’s not criminal charges,” Corey said. “Some of these people need to lose their real estate license. Some of these people need to lose their lending license. The IRS needs to be involved.”

Rules, contracts, and potential investigations

The Community Reinvestment Program is administered through the Department of Commerce. Its multi-million-dollar contract with the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle explicitly addresses conflicts of interest.

“No employee, officer, or agent may participate in the selection, award, or administration of a contract if he or she has a real or apparent conflict of interest. Such a conflict would arise when the employee, officer, or agency, and member of his or her immediate family, his or her partner, or an organization which employs or is about to employ any of the parties indicated herein, has a financial or other interest in or a tangible personal benefit from a firm considered for contract.”

There is no clause that says disclosing a conflict of interest ameliorates it, as Bascomb Green suggested.

In an official statement, a Commerce spokesperson told unDivided that it takes “all complaints and allegations of misconduct very seriously. We are reviewing program records and will take appropriate action should malfeasance be discovered.”

Reached for comment, Commerce Director Joe Nguyen was more candid.

“The public deserves accountability and transparency. We appreciate that (the whistleblower) raised this issue,” he said. “We are taking action.”

Nguyen is in an interesting position. As a former state senator, he co-sponsored the bill that created the Community Reinvestment Program. But as the newly-appointed Commerce Director under Governor Bob Ferguson, he’s now seeing the administration of that program – and others – in a new light.

“What we found when I came in wasn’t acceptable and I also think there wasn’t enough rigor or accountability for how programs were run before I got here,” he said. “I don’t think that’s fair to the people of Washington state or the people we serve.”

Nguyen said he is pushing for added oversight of state contracts, which includes a centralized contracts and compliance team.

“We’ve been working hard to clean up a lot of things,” he said.

As for the contracts involving Community Reinvestment Program funds?

“There are things that are happening that we can’t always say out loud.”

Interestingly, after months of trying to get the attention of someone in state government, Corey only recently received an email from an investigator with the Office of Attorney General Nick Brown. A copy of that email was provided to unDivided to verify its authenticity.

Corey officially spoke with the investigator on October 17.

While it’s unclear whether any of the organizations involved committed a crime by awarding themselves or their family members taxpayer funds, the involvement of the Attorney General’s Office seems to suggest some level of concern.

In an email, a spokesperson for AG Nick Brown said the office “has a longstanding policy of not confirming or denying potential investigatory matters.”

Only scratching the surface

This story only covers a fraction of the evidence in Corey’s binder – which implicates more than a dozen local BIPOC nonprofits. There are also facets of the Community Reinvestment Program that neither unDivided nor Corey have even started looking into.

In addition to down payment assistance and personal debt reduction, CRP helps with small business loans, crime prevention, legal assistance, reentry, and other services.

It’s enough to keep every news reporter in the state busy for the rest of the year, if they are willing to scrutinize diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. Such programs, created amidst the post-Goerge Floyd race and social justice movement, have gone notoriously unscrutinized for fear of being accused of racism.

There have been a few exceptions.

KOMO’s Chris Daniels recently reported on the questionable spending habits of a nonprofit tasked with implementing the state’s “digital equity” efforts.

Key to such stories gaining traction is the willingness of people within communities of color to speak up and demand better of the organizations that claim to serve them.

The mother we introduced you to earlier, whose 27-year-old son was given the runaround by the Urban League of Metropolitan Seattle, said she isn’t hopeful that the organization will correct its behavior without outside intervention.

“I pray that the Urban League can get itself together,” she said. “But at this point, I think they’ve done so much damage to the community that they’re not coming back from this.”

A long time coming

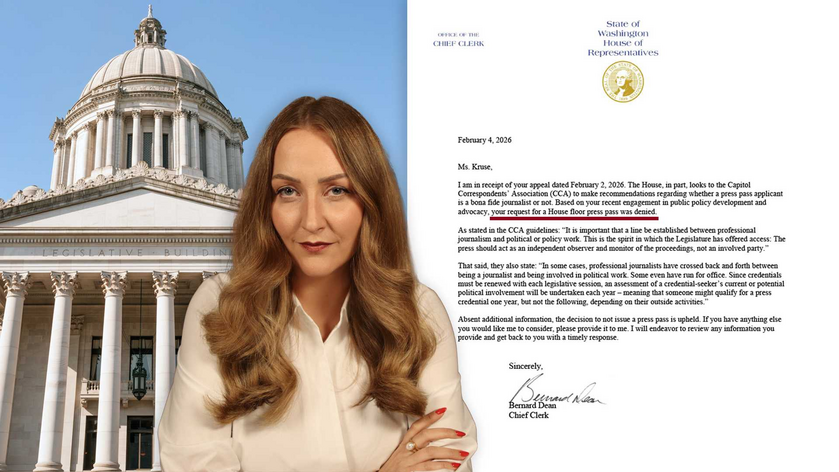

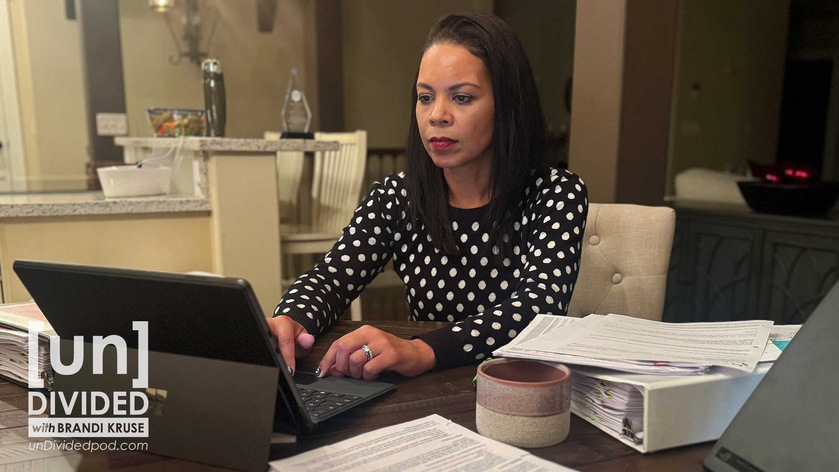

Several months after we first met in her garage, I paid Corey a visit at her home. We went over a few final documents in preparation for publishing this story.

She seemed nervous, but vindicated.

“This is my first time really getting my voice heard,” she told me. “So much has been said about me.”

As with most whistleblowers, Corey has paid a price for speaking up.

When she first raised concerns internally, she was mostly ignored.

Then, she took her fight to her personal Facebook page.

What followed was an all-out assault on her character.

Complaints were filed to try to get her license revoked. Her boss received email complaints. She photographed suspicious cars outside her house. A text message from Aysia Williams demanded she remove posts, or the police would get involved. Corey went as far as to file an anti-harassment order.

When Corey decided to resign in protest from several of the BIPOC nonprofits she belonged to, citing “retaliatory complaints and retaliatory behavior,” she was publicly accused of having a mental health breakdown and acting out because she was only “half black.”

In one email, Washington State Housing and Finance Commission Chair Nicole Bascomb Green admitted to making a remark about Corey’s mental state during a Zoom meeting.

“I shared my thoughts with Corey in front of five other people around her mental state, so this is not a surprise to her or the people who was in the virtual room when I shared it. I stand by what I said, and no amount of outrageous emailing will change my stance,” Bascomb Green wrote, trying to justify making a public pronouncement about her perception of someone’s mental health.

It’s worth noting that in January 2025, months before she started voicing concerns, Corey was honored by her peers with the Western Washington Realtist Vanguard Award.

“I’ve poured my heart into serving the black community,” said Corey, who initially supported the Community Reinvestment Program as a pathway toward helping people build the American dream.

Instead, it left her devastated and angry.

“It’s been misused. It’s enriched certain people,” she said. “I don’t think this is ever what it was meant to do. And to me, that’s heartbreaking.”